yet another iterative root finding algorithm. Combination of Regula Falsi and Newton-Raphson

1. The Core Idea: Parabola, not a Line

-

Regula Falsi (False Position) approximates the function by drawing a line (a 1st-degree polynomial) through two points, and .

-

Newton-Raphson approximates the function by drawing a tangent line (also a 1st-degree polynomial) at one point, , using the derivative.

-

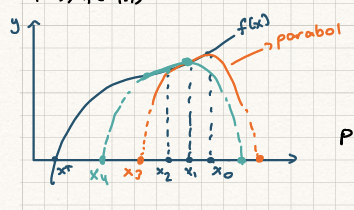

Müller’s Method takes this one step further. It approximates the function by drawing a parabola (a 2nd-degree polynomial, ) that passes through three initial points: , , and .

So,

-

We start with three guesses: , , and .

-

We draw a unique parabola (the blue curve) that perfectly intersects (the orange curve) at all three of these points.

g(x0) = f(x0) and such.

-

A parabola can intersect the x-axis at zero, one, or two points. We find these intersections.

-

Our new guess, , is the intersection that is closest to our last guess ().

-

To find the next guess (), we would “forget” the oldest point () and repeat the process using the points .

The mathematics

The goal is to find the roots of the parabola as our new approximation.

Step 1: Define the Parabola in a Clever Way

Instead of the standard , the notes use a form centered around the most recent point, (in the graph’s first step, this would be ). This is Newton’s form of an interpolating polynomial:

This form is much easier to work with. We find the coefficients by forcing the parabola to pass through our three known points:

Plugging into the equation is very simple:

.

So, we instantly find .

We can then use the other two points to create a 2x2 system of equations to find and . The notes skip this algebra and just state, “Now we know coefficients.”

Step 2: Find the Zeros of the Parabola

We need to solve for our next guess, .

This is just a quadratic equation for the step size . Using the standard quadratic formula , we get:

Step 3: A More Numerically Stable Formula

The standard quadratic formula can be bad for computers. If is very large compared to , then . This means the numerator might become , a problem called catastrophic cancellation that destroys precision.

To fix this, the notes use a common trick: multiply the numerator and denominator by the conjugate (as noted by “eşlenik ile çarp”):

-

The numerator becomes:

-

The denominator becomes:

Canceling the term gives the new, more stable formula shown on the slide:

This formula has “two possibilities” (the ). The * note explains how to choose:

-

We pick the sign in the denominator () to be the same as the sign of . For example, if is positive, we use .

-

This forces the two terms in the denominator to add together, making the denominator’s magnitude as large as possible.

-

A larger denominator gives a smaller step size , which corresponds to the root of the parabola that is closest to our current guess .

3. Convergence

The final note, “The order of convergence is (konu dışı - off-topic),” is a key takeaway.

-

Regula Falsi is linear ().

-

Newton-Raphson is quadratic ().

-

Müller’s Method is superlinear ().

It is significantly faster than linear methods and, while not as fast as Newton’s method, it has a major advantage: you do not need to calculate the derivative , which can be difficult or impossible for some functions.